POPULATION GROWTH AND AGRICULTURE IN INDIA

An analysis by S S Sangra, Former Chief General Manager of NABARD

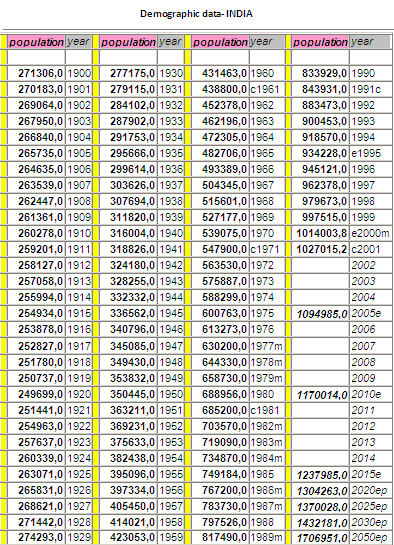

India occupies 2.4% of the world’s land area and supports over 17.5% of the world’s population. India has more arable land area than any country except the United States and more water area than any country except Canada and the United States. Indian life, therefore, revolves mostly around agriculture and allied activities in small villages, where the overwhelming majority of the population lives. As per the 2001 census, 72.2% of the population lives in about 638,000 villages and the remaining 27.8% live in more than 5,100 towns and over 380 urban agglomerations. In 1901 the world population was 1.6 billion. By 1960, it became 3 billion, and by 1987, 5 billion and in 1999, 6 billion. Currently, one billion people are added every 12 – 13 years. When we see the population growth in India as shown in the table below, it will be observed that while the population of the country was 27.13 crore in the year 1900, it decreased to 26.31 crores in 1925 and increased to 35.04 crores in 1950 and 36.23 in 1951. From here onwards the population growth took exponential proportions of growth to 43.88 crores in 1961, 54.79 crores in 1971, 68.52 crores in 1981, 84.39 in 1991, and 102.70 crores in 2001.

Particulars: The main source of the data prior to 1950: KB. Some of the data prior to 1902 with higher figures are for the whole area of British India, which included also Pakistan and Burma. File created on 1997-01-07; revised on 2000-12-10; last modified 2003-07-16 by Jan Lahmeyer With over 115, 00, 00, 000 people, India is currently the World’s second-largest populated Country. India crossed the one billion marks in the year 2000, one year after the World’s population crossed the six billion thresholds. It is expected that India’s population will surpass the population of China by 2030 when it would have more than 153 crores of the population while China would be no. two with a population of 146 crores. Since 1947, the population has more than tripled which has resulted in increasingly impoverished and sub-standard conditions growing segments of the Indian population. In 2007, India ranked 126th on the United Nation’s Human Development Index, which takes into account social, health, and educational conditions in a country. Although we are second to China in population, our country is adding almost an entire Australia each year, while literacy and girl child awareness is growing only at a few percentages, illiteracy, unemployment, poverty are increasing in leaps and bounds. Yes, the government has taken steps to curb the population boom, but its effects will be visible only a few years down the line as and when the rules percolate to the rural regions of India, where more hands mean more income is the nature of thought everyone pursues. Notwithstanding that it affects the entire country and only leads to an increase in poverty in that home and every home that thinks the same especially in Rural India. Overpopulation does not depend only on the size or density of the population but on the ratio of population to available sustainable resources. It also depends on the way resources are used and distributed amongst the population. If a given environment has a population of 10 individuals, but there is food or drinking water enough for only 9, then in a closed system where no trade is possible, that environment is overpopulated; if the population is 100 but there is enough food, shelter, and water for 200 for the indefinite future, then it is not overpopulated. Overpopulation can result from an increase in births, a decline in mortality rates due to medical advances, from an increase in immigration, or from an unsustainable biome and depletion of resources. That nothing has been done in India about the population control. After India became independent, population growth was seen as a major impediment to the socio-economic development of the country and restricting the population growth was seen as an appropriate development process related to economic development. At the same time, it was felt that a small family would benefit both the individual family, the Nation as such as well as the women’s health. In 1952, a sub-committee appointed by the Planning Commission asked the government to provide sterilization facilities and contraceptive advice through existing health services, in order to limit family size. The family planning and population control measures were instituted abundantly and effectively till the 1980s but after that (Sanjay Gandhi and Bansi Lal episode) the whole political, bureaucratic, social and voluntary setups in the country seem to have shut their eyes towards this issue and virtually closed this chapter once for all. The population of the country is increasing by leaps and bounds without anybody’s botheration. Gone are the slogans of the 70s and 80s that HUM DO HAMARE DO and the PAHLA BACHA ABHI NAHI, DO KE BAD KABHI NAHIN, and where do we see the RED TRIANGLE on the walls in the country today. The worst sufferers are the poor, as they, not only increase larger in number due to ignorance but their economic status further gets deteriorated. The government needs to put in place an effective population control system with an aim to formulate a policy that every family living in the country to limit their family size to 3-4 irrespective of the caste, creed, religion, community or region. The unwieldy growth of the population has affected the living conditions of the people. The time has come when future citizens while in educational institutions should understand issues related to the population explosion and the consequential problems. The centralization of whatever little family planning programs the country has, is often preventive due to stark considerations being given to regional differences. Centralization is, to a large extent, due to sole reliance on the central government’s funding. As a result, many of the goals and assumptions of national population control programs do not correspond exactly with the local psyche and attitudes toward birth control. In a large part of India, people have a strong preference for sons which leads to avoidable population growth. They have a feeling that more sons will assist them as farm labor and security in old age but it is hardly true. An important family planning program in India is the Project for Community Action in Family Planning. Located in Karnataka, the project operates in 154 project villages and 255 control villages. All project villages are of sufficient size to have a health sub-center, although this advantage is offset by the fact that those villages are the most distant from the area’s primary health centers. The project is much assisted by local voluntary groups, such as the women’s clubs. The local voluntary groups either provide or secure sites suitable as distribution depots for condoms and birth control pills and also make arrangements for the operation in sterilization camps. Data provided by the Project for Community Action in Family Planning show that important achievements have been realized in the field of population control. India is facing an intense problem of population outbursts. People are experiencing a crisis such as a climate change, shortage of food, and also a severe energy crisis. Our civilization is being squeezed between rising population densities. It can be said that if such trends continue, there will be a severe shortage of food supply not at a very distant future. While in certain places, there is a shortage of drinking water, there are areas that suffer due to devastating floods every year. Village people have started migrating to cities where they have hopes to get some water and employment. Today a beginning seems to have been evident of fights for food, water, and place to live. The importance of this National issue needs to be understood by one and all as soon as possible. A very strong, determined, and effective steps need to be initiated and instituted by the people themselves, the Government, Voluntary agencies/NGOs, Religious Heads, Educational Institutions, Corporate, and other Social Organizations. Sooner the better. People should on their own restrain themselves to produce more children voluntarily to sustain a better quality of life not only for themselves but also for their children and the Nation and the future generations. Otherwise, the future generations are quite likely to curse their forefathers for leaving an unmanageable legacy of a huge population who has to struggle every day to live their life peacefully and comfortably. During the last decade, there has been a substantial decline in the birth rate. The reasons for decline vary from society to society; urbanization, rising educational attainment, increasing employment among women, lower infant mortality are some major factors responsible for the growing desire for smaller families. The pressing need of the day is to create ideal conditions for acceptance of the need for stabilizing the population and how it is an essential element of human welfare and development. The solution to this lies in the spreading of education and enlightenment, and in the empowerment of women. The population control program is also essential from the environmental and energy crisis point of view. There could be dangerous consequences if this issue is not attached due importance. Many other factors are also directly or indirectly associated with over-population like shortage of education and health facilities, employment opportunities, unemployment, and associated socio-economic problems. Many young men and women do not get employment according to their education therefore either they feel disgusted or they involve in criminal activities and become drug peddlers like anti-social activities. Global warming is also related to overpopulation. To control global warming, the population must be controlled. As the population grows, the demand for the consumption of energy such as electricity, automobiles, and other energy resources increases which in turn affects nature. Many countries in the world are responsible for global warming, contributing greenhouse gas emissions primarily from transportation, industry and power plant, etc. The other thing that people should be concerned about is the infrastructure. All of us should understand that places are getting smaller and smaller as the population grows. Places, which once held beautiful landscape, have been turned into mega housing complexes to house the increasing number of people. The population also affects the education system. Today, education is very expensive and few people can afford to attend colleges or even high school. The shortage of seats in the colleges and universities are limited and many parents afford to bear the cost of education of more than two children. Hence this is another reason that people should keep smaller families so that they can afford better facilities for their children. However, the burden on the education system created by an increasing population can be alleviated by colleges with accelerated degree programs such as Baker University. India is facing an intense crisis of resources. There is fierce competition for the nation’s limited natural resources leading to quarrels between states, between communities, and even families. Our land and water resources are being exploited to the hilt. The exploitation of mineral resources is threatening forests, nature reserves, and ecology. Seventy percent of the energy resources need to be imported putting constant pressure on us to export more or face currency devaluation. Overuse of resources is contributing to natural disasters occurring more frequently and with greater devastation. For many Indians, life is a big struggle just to put together the bare essentials for survival, and shortages of resources work most against the poor and underprivileged. Even as sections of India’s lower-middle-class struggle with scarcities, it is the poor and vulnerable sections of society who suffer the most. It is a well-known fact that the biggest curse to the lives of millions of Indians in poverty. Though the rural poor have always been a deprived lot, their urban counterparts are not an inch better off. Having migrated to towns and cities in search of a better life, they now survive under the most appalling of living conditions, with scant regard to the basics of cleanliness and hygiene. Resources and most important the awareness of healthy living habits is woefully lacking. The problem of a large population in India is probably due to the government’s inability to implement FAMILY PLANNING policies. Successive governments have failed to attach due importance to the issue and tackle this problem which has resulted in a tremendous rise in population in the country. Politicians don’t seem to be interested in the welfare of the country and more often than not relegate such issues as unimportant while trying to deal with other issues, scarcely realizing that most of the problems the country faces today are due to the huge population. Lack of sex education in India also has a huge role to play in the population explosion that has followed since independence. Providing access to sex education and having adult education programs is the least the government could do to curb the rise of the population. Another factor contributing to population growth is the issue of child marriage. Though the government has an anti-child marriage policy and has specified minimum age for both males and females to get married at, this policy isn’t being strictly implemented at the grass-root level. Child marriage is still rampant in India. These are just a few of the issues I think the country needs to resolve before embarking on any other mission so to speak. The root cause of most of the problems India faces is the population and once this is dealt with other things should fall into place. Greater education, awareness and a better standard of living among the growing younger age group population would create the required consciousness among them that smaller families are desirable; if all the felt needs for health and family welfare services are fully met, it will be possible to enable them to attain their reproductive goals, achieve a substantial decline in the family size and improve quality of life. But what are we as the citizens of the country doing to contain and snub the problem. We have to get up and stand together and fight this predicament changing it from problem mode to solution mode. The simplest way to help is to go to the homes of the uneducated and teach the lady of the house. Each and every responsible citizen of the Country needs to involve him/herself in educating the unaware population of the ill effects and consequences of the rising population and the dire need of the population control and family planning measures etc., in whatever capacity he or she can. It has to be assumed as a National Urgency and taken up on a war footing basis. There is no room for any sort of complacency or lethargy in solving this THE PROBLEM of the Nation. We can make groups or join an NGO and cover different areas in our vicinity so that more and more people can be taught about this most urgent and burning issue.

Agriculture Situation in India

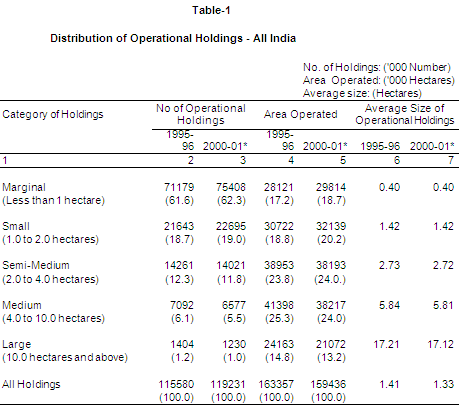

The population growth is speedier in rural India in general and in the central states of the country in particular. The rising population is also leading to the fragmentation of landholdings when land is divided between the future generations. The resultant effect is that the no of land holdings in India has increased from 11,55,80000 in 1995-96 to 11,92,31000 in 2000-01. India has become a land of small farms, of peasants cultivating their ancestral lands mainly by family labor and, despite the spread of tractors in the 1980s, by pairs of bullocks. About 50 percent of all operational holdings in 1980 were less than one hectare in size which had increased to 62.3% in 2000-1. About 19 percent fell in the one-to-two hectare range, 16 percent in the two-to-four hectare range which reduced to 11.8% in 2000-1, and 11 percent in the four-to-ten hectare range which had also reduced to 5.5% in 2000-1. Only 4 percent of the working farms encompassed ten or more hectares in 1980 but this had also reduced to barely 1% in the year 2000-1. This amply speaks of the dwindling size of the landholdings in India as can be seen from Table-1 below.

Note : Figures in parentheses indicate the percentage of respective column total.

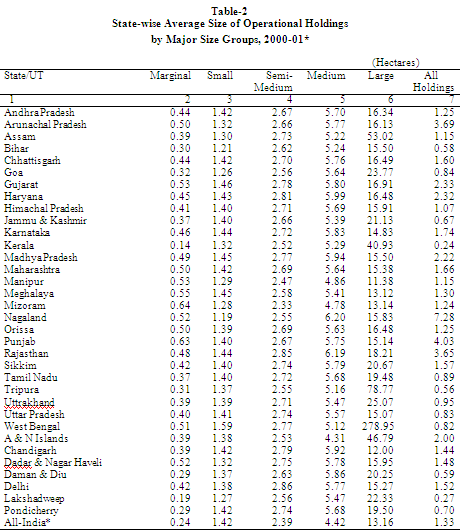

- Excluding Jharkhand Source: Agricultural Census Division, Ministry of Agriculture, New It will be observed from table-1 above that while overall no. of agriculture holdings in India increased from 115580000 in 1995-6 to 119231000 in 2000-01 the increase was sharper in the less than 1 ha. holdings (from 71179000 to 75408000) and 1 to 2 ha. (21643000 to 22695000) categories. In fact, there was also a substantial decline in the no. of holdings in the case of holdings’ size above 2 ha. (22757000 to 21828000) This implies that gradually the no. of smallholdings is on the increase in the Country due to the rising population and the consequent division of the landholdings. It would be observed from Table-2 below that the all India average size of the landholding has also reduced from 1.41 ha. to 1.33 ha. between 1995-6 to 2000-01 and by all probabilities the average size landholding presently would be nearly 1.25 ha. It would also be seen that 62% of the total landholdings are marginal holdings below 1 ha with the average size being .40 ha i.e.1 acre per family in the year 2000-01. One can imagine the situation prevailing now, after 10 years of the last census, which would have gone still smaller with the trend set-in in the past. Although farms in India are typically small throughout the country, the average size holding by state ranges from about 0.5 hectares in Kerala and 0.75 hectares in Tamil Nadu to three hectares in Maharashtra,3.65 hectares in Rajasthan,4.03 ha.in Punjab and highest of 7.28 ha.in Nagaland, as shown in table no. 2 below. Factors influencing this range include soils, topography, rainfall, rural population density, and thoroughness of land redistribution programs in India.

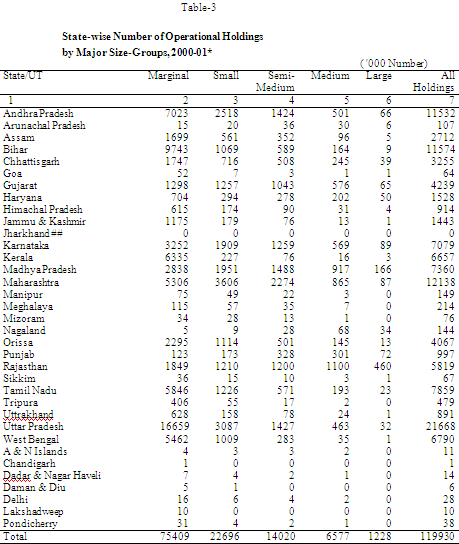

Note : 1.* No data available for Jharkhand 2. Includes institutional holdings also. Source: Agricultural Census Division, Ministry of Agriculture, New Delhi. Analysis of data at the household level in Khabra Kalan village in the Thar desert of India revealed that the landholding size is halved every 20–30 years due to the subdivision of landholdings. The subdivision is caused by the equal sharing among sons at the time of inheritance based on the succession laws and attributed to the increase in the village population. The shrinking land holdings resulted in a shortfall of food on small farms; 12% in cereals and 42% in pulses, promoted continuous cultivation and the increase of monoculture and deteriorated the land productivity through its effect on the soil fertility and land management. When the state-wise position is reviewed as per the details given in Table- 3 below it is observed that out of the total holdings of 11.99 crores in the country 2.17crore (more than 18%) holdings are only in the state of Uttar Pradesh followed by 1.21 crore in Maharashtra, 1.16 crore in Bihar, 1.15 crore in A.P., 73.6 lakh in M.P., 70.8 lakh in Karnataka, 67.9 lakh in W. Bengal, 66.6 lakh in Kerala whereas in Haryana the no. of landholdings was 15.28 lakh and 9.97 lakh in Punjab. The percentage of marginal farmers i.e. landholding size less than 1 ha. was highest at 95.2% in Kerala followed by Bihar at 84.1%, J&K at 81.4%, W. Bengal at 80.4%, U.P. at 76.9%, Tamil Nadu at 74.4% while, on the other hand, Haryana had 46.1% of marginal holdings, Maharashtra 43.7%, Gujarat 30.6%, and Punjab was the lowest at 12.3% among the major States in India. It would be interesting to observe that the proportion of semi medium to medium holdings is the highest at 629000 (63 %) out of the total holdings of 997000 in Punjab whereas in the whole country the same is 17.2 % and in Kerala, it is 1.3%, in W. Bengal 4.6%, in Bihar 6.5%, in UP the same is 8.9. % and, 9.7 % in Tamil Nadu. Even in Haryana and Rajasthan, the proportion of semi medium to medium farmers is 31% and 39% respectively. This speaks of the comparative affluence of farmers in Punjab and Haryana with reasonably big size of the farms as well as the productivity levels which is high of course due to the availability of the irrigation at virtually no cost, adoption and availability of H.Y.V seeds and fertilizers, etc. and of course the passion for farming of the hard-working farmers in the region.

- includes institutional holdings also.

Data for the year 2000-01 not collected.

Note: The sum of States/ UTs may not exactly tally with all-India total due to rounding off. Source: Agricultural Census Division, Ministry of Agriculture, New Delhi. Over seventy percent of India’s population still lives in rural areas. There are substantial differences between the states in the proportion of the rural and urban population (varying from almost 90 percent in Assam and Bihar to 61 percent in Maharashtra). Agriculture is the largest and one of the most important sectors of the rural economy and contributes both to economic growth and employment. Its contribution to the Gross Domestic Product has declined over the last five decades from 42% to 18% but agriculture still remains the source of livelihood for nearly70 percent of the country’s population. A large proportion of the rural workforce is poor and consists of marginal farmers and landless agricultural laborers. There are substantial unemployment and underemployment among these people; both wages and productivity are low. This in turn results in poverty; it is estimated that 380 million people are still living below the poverty line in rural India. Though poverty has declined over the last three decades, the number of rural poor has in fact increased due to population growth. Poor tend to have a larger family size which puts an enormous burden on their meager resources and prevents them from breaking out of the shackles of poverty. In States like Tamil Nadu where replacement level of fertility has been attained, population growth rates are much lower than in many other States; but the population density even there is high and so there is pressure on land. In States like Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh population is growing rapidly, resulting in increasing pressure on land and resulting in land fragmentation. Low productivity of small landholders leads to poverty, low energy intake, and undernutrition, and this, in turn, prevents the development thus creating a vicious circle. Productivity in agriculture is mainly dependent on two sets of factors, they are technological and institutional. Among the technological factors are the uses of agricultural inputs and methods such as improved seeds, fertilizers, improved plows, tractors, harvesters, irrigation, etc. All these factors help to raise productivity, even if no land reforms are introduced. On the other hand, the institutional reforms include the redistribution of land ownership in favor of the cultivating classes so as to provide them a sense of participation in rural life, improving the size of farms, providing security of tenure, regulation of rent, etc. Today, land reform in rural India is at the crossroads. Despite the inequity, the constituency advocating land reform is weakening day by day and the number of people pushing for revocation of land ceilings is increasing. In the ’90s, as India embraced economic liberalization, a growing consensus emerged among the vocal opinion-making class that ceilings on land have proved to be inefficient economic tools and hampered the development of agro-business. Increasingly, there is a demand for the re-examination of the land reform issue. It is also being argued that the liberalization of tenancy would not only increase the availability of land in the lease market but would also increase the poor people’s access to land. The average annual rate of growth of agriculture in the last five years was 1.87 percent—possibly the lowest since Independence. Compare that with the 5-per cent growth in the mid-1980s, described as the golden period, and one would understand why this is now turning out to be the worst of times for agriculture. In the last decade, there have been signs of stagnation everywhere. Overall land under foodgrains has remained at 120 million hectares and is showing signs of dropping further. Public investment in agriculture as a percentage of GDP has dropped from 3 percent to around 1.7 percent. The addition to irrigation was very low compared to previous decades. Groundwater tables have dropped rapidly and the shortage of water for farming has reached crisis levels. Worse, there has been no technological breakthrough that can boost the yields of major food grains to produce a second Green Revolution. Not surprisingly, a recent national sample survey showed that 40 percent of the farmers want to opt-out of their current profession. And that every year, over 20,000 farmers commit suicide out of despair over failing crops and impossibly high debt. “The situation is deteriorating rapidly and the entire farming sector is heading for a total collapse if no rapid remedial measures are taken,” warns eminent agriculture scientist M.S. Swaminathan, Uttam kheti, maddham beopar, bhatth Chakri (Farming is the best occupation, business is second best and working for someone else is the worst), goes an age-old saying in Punjab. But Sital Singh, 73-old-farmer from Umedpur village in Ludhiana district, feels it no more holds good as farming has become a losing proposition. The deep crises on his weather-scarred face reflect his state of distress. “Agriculture is now just another name for the struggle for survival,” he says with an earthy flourish. Sital owns five acres of land and cultivates 10 more acres of rented land. Until seven years ago, his wheat yield was up to 25 quintals an acre. But it has dipped to 16 quintals over the years. “Everything is going up except my income,” he says, referring to the escalating cost of fertilizers, diesel, seed and land lease rates. “Land is behaving like a drug addict. It’s demanding more but delivering less and less,” he observes. Yields in the major wheat-growing states of Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana have touched peak levels and in many zones are facing a decline. In Punjab, the yield from one hectare has dropped from 4,700 to 4,000 kg a hectare in two decades. The decline is largely attributed to an “aging” wheat variety WL 343, which has been in use since the mid-’90s. Yields of other food grains to have stagnated. In the major rice-growing states of West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and Punjab, yields have hovered at around 1,900 kg per hectare. Yields of pulses have reached a plateau at around 600 kg per hectare and the total production has not exceeded 15 million tonnes. A new high-yielding variety is being introduced, but it will take a while to stabilize. With demand for pulses pegged at around 18 million tons, India has become the world’s largest importer of the commodity. In oilseeds, though India has doubled its production in the past two decades to 26 million tons, increased consumption as a result of higher incomes has led to a shortfall of 3 million tons, necessitating a constant flow of imports. The Green Revolution was aimed at the better-endowed regions. For millions of farmers languishing in the drylands, constituting more than 70 percent of the cultivable lands, it continues to be a futile struggle. Despite the emphasis on dryland farming during the past several decades, the scenario still remains grim. The undulating topography and the irregular rainfall pattern have combined to aggravate the situation. That the drylands produce about 42 percent of the country’s food shows that the future of farming lies in these areas. Nearly 83 percent of sorghum, 81 percent of pulses, and 90 percent of oilseeds grown in the country come from these areas. The poor yields and the fluctuations in production are indications of the scant attention drylands have received from policymakers and planners. The problem of increasing productivity on drylands has serious socioeconomic implications. With every passing year, the gap between the farmer’s yields in irrigated areas and in the dry farming region is widening. One year of drought is enough to push a farmer into a deep well of poverty for another two to three years. Drought is a recurring phenomenon in arid and semi-arid areas. Fifty years after Independence, life for millions of people somehow surviving in the drylands continues to be worse than before.- Devinder Sharma As if this is not enough, the number of landless in rural areas to have been multiplying over the past few decades, at an estimated rate of two million every year. The rapid expansion in the number of landholdings, with less than a hectare under the plough, has meant an additional 6,00,000 farmers every five years or so. The negative terms of trade for agriculture and the declining public sector investments in farming are indices of the sluggishness in this sector. Pawar Union Agriculture Minister said to India Today that I’ll be frank, unless and until we reduce the burden of population on land, agriculture will not be viable. Developing countries that have succeeded in diverting their population to other sectors have been able to resolve the crisis in agriculture. We have to follow that route. If declining food grain production and access to food remain the two biggest problems confronting the country, there must be something terribly wrong with the way we look at agriculture. With more than 70 percent of the population still engaged in agriculture and allied activities and an equal percentage of farmers tilling an average of 0.2 hectares of land and somehow surviving against all odds, the time has come to set the balance right. Whether we accept it or not, India is gradually moving back to the pre-Green Revolution days of a ‘ship-to-mouth’ existence, when food was largely imported to feed the hungry. It was the political maturity of the then leadership that led to self-sufficiency on the food front. Few will still question what Jawaharlal Nehru once said: “Everything else can wait, but not agriculture.”- Dr. M.S. Swaminathan As mentioned earlier about 62% of the total landholdings in the country are marginal i.e below 1 ha area with the average size being .40 ha i.e.1 acre only and the total area of cultivable land owned by this category of farmers was 29814000 ha in the year 2000-1. This huge arable area of nearly 30 million hectares is virtually contributing a very insignificant quantity of agriculture produce in the National kitty due to the small size of holdings that too fragmented into 2-3 pieces of land. It does not enable the farmer to get good productivity for the obvious reasons of limited resources, traditional cultivation practices, poor access to good quality seeds, fertilizers, irrigation, etc. On top of it whatever little he is able to produce is not even sufficient to meet his own domestic needs. Hence, until and unless he is able to do some additional labor job he is not able to feed his family two square meals a day. The situation is precarious both from the farmers’ point of view as well as for the Country in the sense that such a huge area of otherwise fertile land is virtual of not any use to the Nation. The productivity levels can be nearly doubled if this land is used in a more professional way with better technology and farm management practices etc. The unit size of the land is too small to make it viable by the individual farmer himself. On the other hand, one cannot wish away 62% of the holdings touching the lives of nearly 400 million of the country’s population. It is a great challenge for the Nation to make these units viable and sustainable. The need perhaps is to come together by these farmers, break their land boundaries (“MERH TORNA HOGA”), operate on a large piece of land on the collective farming basis, pool their resources, get technical advice from technocrats, have access to good quality seeds, fertilizers, and other important inputs and follow better farm management practices and try to undertake cultivation on a large scale but collectively so as to achieve the economies of scale and higher productivity levels. It, though, sounds difficult but not impossible and if given a fair trial can lead to definite improvement in the economic status of not only the marginal farmers but can generate a handsome surplus for the Nation as well. The Government and the other developmental agencies can make it happen. The other alternative is to create enough of alternate employment opportunities in the non-farm, off-farm, agro-industries, etc. to shift a large number of agriculture-dependent population to these non-farm and off-farm sector activities so that the manpower load/abundancy on the land can be reduced. This process of shifting the agriculture-dependent population to other sectors has been quite rapid and effective in other developed and developing nations but the same has been rather sluggish in India and hence the rampant unemployment, underemployment, poverty in rural India. In most of the states, non-farm sector employment opportunities in rural areas have not grown much and cannot absorb the growing labor force every year and provide full-time employment. In this context, it is also imperative that programs for skill development, vocational training and technical education are taken up on a large scale in order to generate required employment opportunities in rural areas. The entire gamut of existing poverty alleviation and employment generation programs may have to be restructured to meet the huge and emerging demand for employment in the coming future. It has been seen that despite the best efforts and intentions of the Government as well as the developmental departments/agencies involved in this sector the pace of rural industrialization has been rather dismal probably due to lack of the entrepreneurship, resources, technology, demand and marketing facilities, etc. Even in the field of Agro-Processing, there has been no appreciable progress. Though it has perhaps been thought that the farmers would be involved in the setting up of agro-processing activities but looking at their average landholding size and the level of availability of resources with the individual farmers it is doubtful whether a farmer can venture into this highly capital intensive and risky agro-processing sector. The answer lies in the strength of unity and collective ventures which though seems quite difficult but not impossible provided the leaders show enthusiasm, cooperation, professionalism, technology-savvy, and above all the transparency. The existing industry has been facing problems of low capacity utilization, technological obsolescence, and marketing. It has to work under the constraints of high fluctuations in raw material availability & quality, fluctuating market price, poor technology for handling and storage, inadequate R&D support for product development, high cost of energy and uncertainty in the availability of adequate quantity for processing purposes, inadequate and expensive cold chain facilities and varying requirement of processing conditions from one material to another. Future R&D has, therefore, to focus on the issues of economically producing value-added products and product diversification, besides the issues mentioned above:

- Emphasis should be put on the establishment of new agro-industrial plants in the production catchments to minimize transport costs, make use of lower-cost land and more abundant water supply, create employment opportunities in the rural sector, and utilize/process waste and by-products for feed, irrigation, and manure.

- Infrastructure in the production catchments selected for agro-industrial development should be improved. Because of uncertain grid power supply to rural areas, decentralized power generation using locally available resources may become an integral part of agro-industrial development. Similarly, if the raw materials and processed products are perishable or semi perishable in nature, cold chain technology will have to be established in the area.

- The national plan should provide for the management of agro-industrial activities in the catchment area, both by private companies and individuals as well as cooperatives.

- Financial incentives and support should be provided on a liberal scale to promote the modernization of the agro-processing industry and for establishing new such industries in production catchments.

- Arrangements to supply market information to the farmer and agro-processors should be put in place. References

- Agro-Processing Industries in India—Growth, Status, and Prospects R. P. Kachru Asstt. Director General (Process Engineering), Indian Council of Agricultural Research, New Delhi